We are thankful for this opportunity to transmit our position on the different themes outlined by the UK COP26 President Designate for the upcoming July Ministerial Meeting. We believe that indigenous peoples have crucial stake and contribution to the substance and potential outcome of the upcoming negotiations in Glasgow.

Please find below our expectations and recommendations for the thematic discussions.

1. Protecting people and nature from the impacts of climate change

What outcomes are needed on the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA) at COP26? How can we ensure an effective assessment of collective progress towards the GGA ahead of the Global Stocktake?

There is a need to assess the progress and learning of the different adaptation actions that work, with special attention to locally led adaptation actions by women, indigenous peoples and local communities.

It is important to define the purpose of the GGA. Defining the purpose of the GGA would enable streamlining oversight of progress across all the adaptation workstreams – including planning, delivery, capacity building, technology, and finance.

Greater recognition of adaptation efforts is needed, yet there is currently no consensus on frameworks for assessing adaptation objectives and outcomes. The GGA could provide a framework gathering adaptation evidence globally and deriving insights from its assessment. For example, it could seek to answer questions about the importance of inclusion and engagement with different actors: Has an intervention reached the part of society it intended? How meaningfully have those actors been engaged – who was engaged when and how? What level of agency and authority did actors have? At what stage in the investment cycle did these actors have influence or authority?

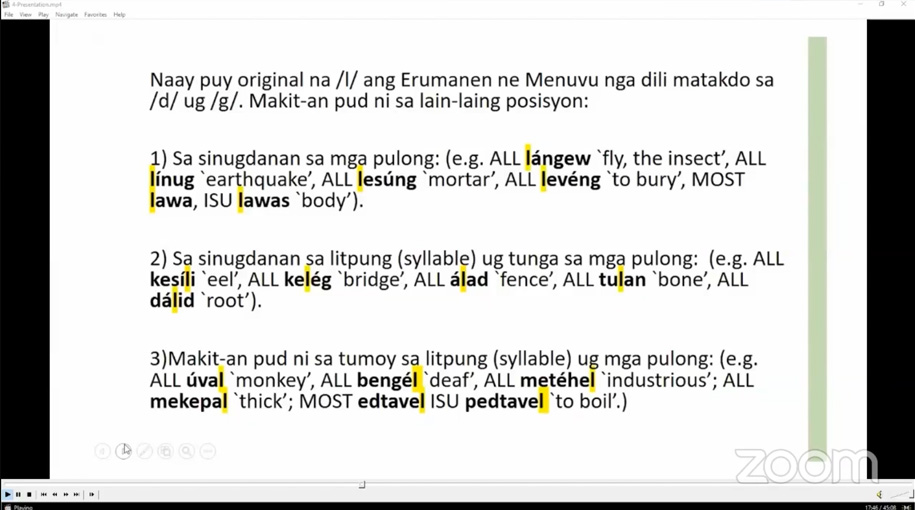

It would also be beneficial for the GGA to review metrics of impacts in adaptation. Who defines what impacts should be? There is a need to shift paradigms and change narratives of when we talk about scale and impacts. Usually, when scale and measurements refer to number of people, amount of tons of CO2eq or how large the geographical coverage of a climate action. But we should redefine scale to look deeper rather than wider to include for example, policy and attitude changes, smaller, locally driven and proven climate actions that can be scaled up, replicated and strengthened. We want also to highlight the need to integrate traditional knowledge of indigenous peoples in climate change adaptation and mitigation actions as stated in Article 7 (section 5) of the Paris Agreement.

The GGA can be a mechanism to drive collective learning through gathering the responses to questions, to collect examples and derive good practice. The GGA could be the basis for understanding how different adaptation interventions enable adaptation; avert, minimize and/or address loss and damage. For indigenous peoples, the GGA could consider working at the Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples Platform (LCIPP) as a mechanisms for exchange and mutual learning.

2. What can be done to improve the quantity, quality, and predictability of finance for adaptation, including improving the accessibility of finance for locally-led action?

A functional definition of climate finance and greater transparency to support transformative change vulnerable countries need to transform their economies and societies to achieve the SDGs in a low-carbon and climate-resilient pathway. to track financial flows is required to help track progress and inform collecting evidence of good practice. This requires strong and agile institutions who can innovative and investigate climate solutions and influence wider development and private finance flows. However, the lack of a clear climate finance definition means donors currently are counting very different things, some of which is incapable of playing this transformative role. So, climate finance is low in quality overall: it is risk averse (as conventional development), fails to build institutional capabilities, and helicopters in solutions.

Prioritize direct and enhanced direct access to climate finance for the most vulnerable countries and peoples : Many LDCs and SIDS struggle to access the small amounts of climate finance that is available. Only 2% of climate finance is committed to the SIDS and only 14% is committed for LDCs. These numbers could be even lower given that of donor reported adaptation finance between 2014-2018, only 17% or US$5.9 billion of adaptation finance invested in LDCs actually had climate adaptation as the primary objective. Less than 20% of donor reported adaptation finance flows to the LDCs. Most of this climate finance is delivered through international intermediaries, who are accountable primarily to donors not to local communities at the frontlines of climate change. For example, 78% of the Green

Climate Funds portfolio (the world’s largest dedicated climate fund) is channeled through international intermediaries. This may be due to under-recognition of the role that direct and enhanced direct access plays in supporting transformative change, instead prioritizing the same business as usual international organizations. To better support direct and enhanced direct access to a range of public, private, and civil society organizations, bilateral donors and multilateral climate funds can:

- Harmonize, streamline, and simplify their access criteria

- place tight time bound procedures and performance measures on direct access

- provide access quotas on direct versus international access

- placerulesoninternationalintermediariestomentornationalandsub-national institutions, especially in specialized fiduciary standards to be able to on-grant, on-lend and invest

- developdedicateddirectaccesswindowsfornon-stateorganisations–including grassroots organizations and local enterprises.

Increase commitments for locally led climate action including direct access mechanisms for indigenous peoples, women and local communities. Including funds for capacity building and institutional support. Climate Finance should be predictable, flexible and long term to ensure sustainability of actions.

It takes significant amount of time to institutionalize transformative change. However, existing climate funds are few, far apart, short term, not scalable, few and project based that are seeking immediate mitigation and/or adaptation results, rather than investing in a change process that will deliver more sustainable and potentially much greater climate action in the long term. Increasing commitment for direct access to climate finance for indigenous peoples should mean:

- Climate finance to be accessed directly by indigenous peoples’ organizations and communities without undergoing through intermediaries

- These should come in terms of grants and not loans

- These should be directly managed by IPs, Lcs and women and should have a built in mechanisms for capacity building and institutional development. Beyond country ownership, the process would be owned by IPs, local communities and

- These should be long term and not far apart or project based

- These should have robust safeguards in place that do not only seek to do-no- harm but also be intentional in their aspiration to do good.

Radically improve precision and granularity climate finance reporting. Reporting should not only include quantity of finance provided by donors to countries, not only their commitments and the actual disbursements but they should also include qualitative indicators of how actors on the ground, including women, indigenous peoples and local communities have been engaged and have benefited. Equally important is to show how these climate funds are respecting human rights in their implementation and contributing to the overall goals of SDGs.

Synergies between climate, environment and development funding: Urgent action is needed to both tackle climate change and address the ongoing loss of nature. There is also need to look at the need to support and protect environmental defenders and ensure that they do not get threatened and criminalized in the exercise of their work. Meanwhile, there is no line between development and climate change. Reducing poverty and increasing capacities of local communities and indigenous peoples to adapt to climate change for them to be able to continue their low-carbon, indigenous livelihoods and support appropriate technologies and innovations.

Loss and damage

- A multi-sectoral approach to integrate L&D risks not only into disaster risk management or climate change activities, not only across all government ministries but includes civil society, humanitarian and development actors, the private sector, indigenous peoples and communities in decision making processes on L&D and that particularly enables locally led

- Supporting institutional capabilities

- Loss and Damage should be on top and separate from adaptation funds

3. Mobilizing finance

How can confidence be built that the $100bn/yr goal will be delivered through to 2025?

We support the call to US$100 billion pledge must be delivered before or at COP26 and ensuring adaptation finance to US$50 billion regardless of funding mobilized for mitigation. The GCF and some bilaterals have agreed that there should be a 50:50 balance between funding for mitigation and adaptation. The UN Secretary General is now calling for this also. The majority of public climate finance committed is for mitigation - renewables and energy efficiency – despite it being far easier to generate a return on investment in these areas. The largest economies are the big emitters but can also attract private investment most easily. Adaptation remains substantially underfunded, receiving only 20% of overall climate finance. Yet, adaptation is more critical to the LDCs and SIDS given their low emissions and high climate vulnerability, and is less able to generate a return – therefore requiring far greater levels of public grant-based financing.

4. Finalizing the Paris Rulebook – Article 6

In relation to the ongoing negotiations in Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, we are concerned that it is now being framed wholly as a market based solution. We want to reiterate that we cannot talk about carbon markets, or carbon in the first place without looking at forests, and the peoples and communities behind them. The negotiations around Article 6 should be reformulated to first and foremost include human rights and indigenous peoples rights, as the Paris Agreement, itself has recognized. Human rights and indigenous peoples rights, using the UNDRIP as a minimum standard, should be central to the discussion of Article 6.

5. Inclusive climate action

Inclusivity is not an option, it’s a must: The activities outlined above must be undertaken in a way that enables inclusive climate action, which means a whole of society approach that includes public, private, civil society institutions, indigenous peoples, women, men and children and marginalized groups

Enhance synergies between climate, nature, and development outcomes to delivery inclusivity: As outlined above, urgent action is needed to address current climate impacts and plan for rising (compound) risks. This includes addressing the ongoing loss of nature and reverse rising poverty and inequality. COVID-19 is adding an extra layer of complexity and risks. Inclusive climate action needs to consider how it can also deliver co-benefits across all these dimensions, to ensure action is inclusive and interconnected.

Contact: Raymond de Chavez (This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.) and Grace Balawag (This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.), Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation Program, Tebtebba Foundation.