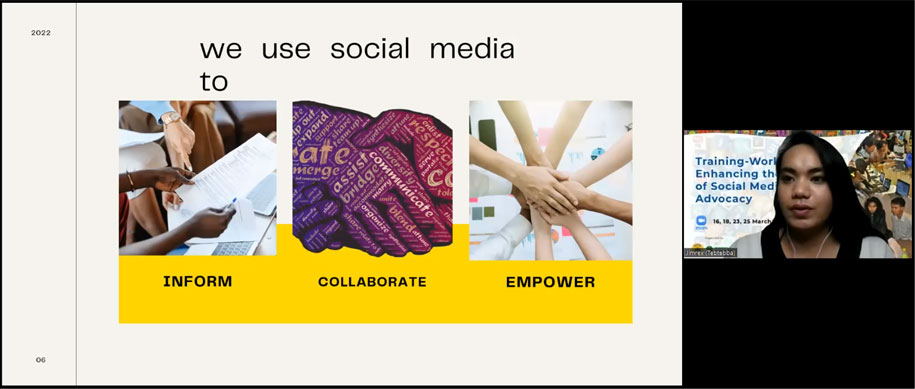

“Social media is critical. As Indigenous Peoples, we use social media to further promote our identity-our culture, our lands and territories, and other resources. We also use it to encourage and fight for the recognition of our rights and our inclusion in the different decision-making processes. We use social media to inform, collaborate and empower.”

Jimrex Calatan from the Strategic Communications and Knowledge Management Department (SCKMD) of Tebtebba shared on the role of social media in advocacy of indigenous peoples' rights during the first day of the Social Media Advocacy Training-Workshop organized by ELATIA Training Institute and the Indigenous Navigator through Tebtebba on March 16, 2022.

Jimrex Calatan, Communications Staff, SCKMD

“Let’s strive to enhance our skills and exchange knowledge” said Maribeth Bugtong-Biano, the coordinator of ELATIA Training Institute as she welcomed the participants. The four-day training-workshop aims to strengthen communications and advocacy work at various levels of ELATIA and Indigenous Navigator partners in amplifying their various development programs and activities while allowing more visibility of Indigenous Peoples in different online platforms.

Maribeth Bugtong-Biano, Coordinator, ELATIA Training Institute

“The world is in crisis right now. We are in a multiple global crisis, and that is why we as Indigenous Peoples need to be political actors.” Helen Biangalen-Magata, Communications Officer of Tebtebba reiterated the need for Indigenous Peoples to be engaged in decision-making processes at all levels. This is because according to her, while Indigenous Peoples have been contributing much to the solution of these problems, unfortunately, they remain to be among the most vulnerable from the impacts of the crises due to their close relationship to their land.

“The goal of Indigenous Peoples as political actors and communications is ultimately for our collective rights as peoples to be recognized, to be promoted and to be fulfilled,” she concluded, thus explaining the importance of social media in advocacy work of Indigenous Peoples.

Helen Biangalen-Magata, Communications Officer, Tebtebba

Five popular social media platforms including Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, LinkedIn and YouTube were discussed and examined in terms of their efficacy as tools for Indigenous Peoples for their advocacy work. The features, advantages and disadvantages of each of these social media platforms were discussed, and an open discussion followed regarding the safety and security of both the social media platforms and its users. The training-workshop concluded with a homework for the participants to be submitted through the Google Classroom.

The second day of the Social Media for Advocacy Training-Workshop is set on March 18, 2022 where the participants will discuss News writing and Creating Picture Quotes.

The training-workshop was held via Zoom with participants from the ELATIA and the Indigenous Navigator Initiative partners. This is being supported by the Bread for the World and The Christensen Fund through the International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA).