Introduction

The importance of national ownership of the Green Climate Fund (GCF) by the main actors in the climate agenda has been part of the negotiations of the Parties, and among them, Indigenous Peoples, as observers. The concept of national ownership of climate issues is based on ensuring a negotiation process that is transparent and adjusted to the social, economic, environmental and cultural reality in each country. The importance of the level of national ownership in climate issues implies having the participation of those actors who are most affected by climate change and especially by those whose mitigation and adaptation actions may have an impact on their territories and livelihoods. In other words, national ownership implies taking measures of national involvement which, then, means making the commitment as their own.

The concept of national ownership has been used in the development cooperation agenda since the 1990s, when the discussion pointed to a paradigm shift from the donor community towards an empowerment of the recipient countries, which meant higher levels of involvement, participation and collaboration of society. This idea has been taken up with greater emphasis in climate finance actions since the signing of the Paris Agreement.[1]

Country Ownership in the Green Climate Fund

The issue of National Ownership has been in the discussion of the Green Climate Fund (GCF) since 2013, when the Board “recognized that the national ownership approach is a central principle for building the Fund's businesses” (decision B.01-13 / 06). By decision B.17/21[2], the GCF Board adopted the Guidelines that, although it does not present a detailed definition of the concept of country ownership, the Board members / alternates highlighted the following components as important[3]:

- The adoption of guidelines that aims to improve ownership in countries;

- Call on the Secretariat, accredited entities, implementing partners and designated national authorities / focal points to follow these guidelines;

- Request the Secretariat to annually evaluate the experiences gained from the application of these guidelines and to continue to improve the guidelines based on lessons learned and observations of current best practices; and

- Decide to conduct a review of the application of these guidelines as necessary, or at least every two years.

One of the most relevant decisions that the GCF Board has taken to implement the concept of national ownership has been the creation of the National Designated Authorities[4] or Country Focal Points. These are usually located in government institutions, acting as links between each State and the GCF. In fact, in the Governing instruments for the GCF, it defines the following: “Recipient countries may designate a national authority. That National Designated Authority will recommend funding proposals to the Board in the context of national climate strategies and plans…. National Designated Authorities will be consulted on other funding proposals for consideration prior to submission to the Fund to ensure consistency with national climate plans and strategies[5]”.

This issue has been highly relevant in the Board's discussions regarding the role of the National Designated Authorities (NDA) and the nomination for accredited entity and non-objection procedures, in such a way that, gradually, it has been integrated into the operational modalities, country programming and structured dialogues[6].

In such a way, the issue of national ownership turns out to be a concept that is implemented through the NDA, which has great decision-making power and offers the country the great opportunity to exercise national sovereignty regarding climate finances for the country.

The foregoing is confirmed, for example, when an Accredited Entity submits a concept note, to be reviewed by the GCF Secretariat, this will request confirmation from the National Designated Authority or the Focal Point that the concept note fits the context and country priorities[7]. In other words, the country in question has the opportunity to exercise the right to define its own vision of development.

Another important decision was B.05/14 of 2013, which reaffirms that the Readiness and Readiness Preparatory Support Program (RPSP) is a priority strategy for the GCF to improve ownership and access of the countries. On the 22nd Board session, a new RPSP strategy for 2019-2021 was approved. This revised strategy, approved in decision B.22/11 has a long-term focus, providing a vision and objectives at the program level.

Another relevant aspect on the issue of national ownership or country ownership is the issue of the involvement of key stakeholders in the participatory processes of consultation, design, implementation and evaluation of projects that are financed by the GCF, as established in the Gender policy, the Indigenous Peoples Policy, and the GCF's Environmental and Social Safeguards Policy and by the Governing Instrument of the GCF.

The policy on Indigenous Peoples approved by the Board also addresses elements of country ownership (decision B.19 / 11):

“This Policy complements best practices for country coordination and multi-stakeholder[8] engagement processes to develop national strategic frameworks… and will apply to these and any future GCF engagement processes. Specifically, this Policy informs the Designated National Authorities and Focal Points that any consultative process through which national priorities and strategies on climate change are defined must also consider the applicable national and international policies and laws for Indigenous Peoples. Furthermore, the criteria and options for coordinating countries through consultative processes should include Indigenous Peoples in an appropriate manner. The requirements of this Policy are part of the relevant standards of the GCF Social Safeguards Strategy (ESS) that accredited entities and States must take into account when developing proposals, as well as monitoring and evaluation after approval”[9].

The GCF guidelines indicate that within the framework of national ownership actions: The financing proposals that are submitted to the GCF must be in accordance with the National Plans for Sustainable Development, the Intended Nationally Determined Contributions at the National Level (INDC) and the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC), Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Actions (NAMAs), National Adaptation Action Programs (NAPA), National Adaptation Plan (NAP) and other adaptation planning processes, as applicable:

- Support long-term planning by identifying climate change financing and investment needs and relevant implementing entities;

- Act as a framework for capacity building at the country level, consolidating all interactions in terms of readiness, project preparation facility (PPF) and funding proposals; and

- Support direct access and foster collaboration between international entities and local institutions, as appropriate.

The GCF has taken initiatives to implement country ownership, for example by improving direct access to financing, as a way to increase the level of national ownership over projects and programs (Decision B.10 / 04. (Annex I, Report of the Tenth Meeting).

The Board, with its decision B.10 / 06, instructed that the Accredited International Entities (IAE), in their accreditation application, will clearly indicate how they intend to strengthen or support possible sub-national, national and regional entities to meet accreditation. Even the GCF included this condition in the accreditation process (Decision B.14 / 08) and the investment criteria (Decision B.07 / 06).

So, why do Indigenous Peoples seemingly continue to be outside the decisions of the GCF? What does it take for Indigenous Peoples to be considered within the framework of national ownership? How do they acquire the capacity to participate?

The answers to these questions could be posed as follows:

First, it must be remembered that in decision B.14 / 08, the Fund confirmed that the principle of country ownership goes beyond the authorities of the national government. This decision "includes ownership by local communities, civil society, the private sector, women's groups, Indigenous Peoples organizations, municipal / village level governments, etc." In other words, the process must be absolutely inclusive.

Second, it is related to “true country ownership” that also depends on full, effective and timely access to culturally appropriate information. The Information Disclosure policy (approved by the Board - Decision B.12 / 35, paragraph a) includes relevant provisions to ensure that Indigenous Peoples are fully and effectively consulted and engaged. Timely and culturally appropriate information is also essential to ensure the principle of Free, Prior and Informed Consent with respect to any activity that occurs on the lands and territories of Indigenous Peoples.

Third, to empower the countries, their national and sub-national entities, the RPSP must be developed, to comply with the capacity requirements, as well as with the norms and safeguards, especially the fiduciary, social, environmental, gender, labor and participation of people and communities. This is necessary because until now it has been seen that NDAs and many State officials related to these issues are unaware of the international and national legal framework on the rights of Indigenous Peoples, which represents an enormous limitation to ensure the involvement of these peoples. Furthermore, it is necessary for the RPSP (Readiness and Preparatory Support Program) to finance actions aimed at having a wide dissemination at the national and subnational levels of the GCF's Indigenous Peoples Policy.

Fourth, the accreditation policy has, so far, enabled 79%[10] of GCF funds to be allocated to accredited international entities, positioning them in the role of intermediaries.

To strengthen national ownership, a 180-degree turn could be made, such that the implementation and execution of projects and programs is undertaken only by national and sub-national entities that comply with solid fiduciary, social and environmental standards, gender and labor norms and safeguards to guarantee the full and meaningful participation of individuals and communities. In this way, accredited international entities would assume an executing function only in a few very exceptional circumstances, either due to their technological complexity or because they are multi-country projects or programs.

Fifth, it has already been difficult to achieve a financing balance between adaptation and mitigation, but what if the Board makes the decision to define a financing ceiling for international entities and a floor for the allocation for national and sub-national entities in relation to total funds of the GCF?

Sixth, most of the consultation and engagement activities are related to NDAs, GCF Board members, external experts and focal points. The only possible opportunities for Indigenous Peoples and civil society to participate is through an online questionnaire or in structured dialogues if these include elements related to the assessment.[11] This situation could be overcome in other ways, for example with financial resources from the GCF that allow local and national participatory processes. For its part, the IEU has found that the GCF's policies related to stakeholder participation are deficient since they do not start from a properly clear definition of the concept of country ownership. For now, it has been easy for NDAs to issue letters of no objection, based solely on the consideration that the proposals fit with national development plans. However we do not know the levels at which important stakeholders - such as indigenous peoples, women, youth - are taken into account. There is no clear guideline from the GCF on how AEs should report these levels of participation.

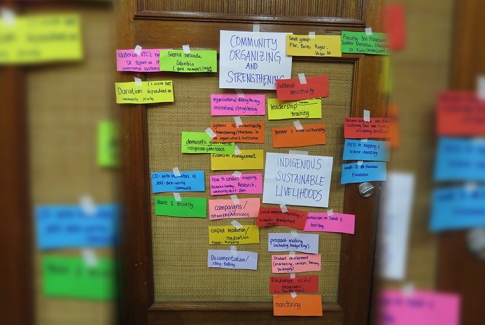

The tradition for decades has been that the decision-making process has been top-down. Nonetheless, the current practice delves on the creation of processes that involve stakeholders (those who have an interest in a decision or are affected by it) and recognize the importance of public attitudes, perceptions, beliefs and knowledge.

Stakeholder engagement has become a critical component of many state and local agency operations that are now requiring major stakeholder involvement in some form. Methodologically, there is no pattern the need to involve stakeholders, However, there is awareness that stakeholder participation is important and has many benefits.

A great challenge that will continue to exist is that "[c]ountries retain a lot of flexibility to institutionalize their own processes and, therefore, determine what national ownership means for them." This is highly problematic, as it would mean that unless some minimum common criteria and standards are clearly adopted and implemented, there may never be a homogeneous level of compliance in stakeholder engagement and even less so in Indigenous Peoples’ engagement in different countries.

Clearly, the recommendation to the NDAs and to the GCF itself is that they should apply section 7.1.1 of the Indigenous Peoples Policy which calls on accredited entities and executing entities to interact proactively with the relevant peoples to guarantee their ownership: Accredited entities will consult with indigenous peoples on the cultural appropriateness of proposed services or facilities and will seek to identify and address any economic, social, or capacity constraints (including those relating to gender, the elderly, youth, and persons with disabilities) that may limit opportunities to benefit from or participate in the project.

Finally, it should be noted that there is no one-size-fits-all approach when involving stakeholders including the collection of their contributions or recommendations and then incorporating that information into the decision-making process. The contexts vary and each one must be analyzed: the actors have different interests and the national legal frameworks may either facilitate or not the participatory processes. For there to be a correct sense of country ownership, it is absolutely necessary to carry out participatory processes and support a due process of consultations.

---

[1] Asfaw, Solomon, Cory Jemison, Aemal Khan, Jessica Kyle, Liza Ottlakán, Johanna Polvi, D4etlev Puetz, and Jyotsna Puri (2019). Independent Evaluation of the Green Climate Fund’s Country Ownership Approach. Evaluation Report No. 4, October 2019. Independent Evaluation Unit, Green Climate Fund. Songdo, South Korea.

[2] GCF. 2017. GCF/B.17/21. Decisions of the Board – seventeenth meeting of the Board, 5 – 6 July 2017. https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/gcf-b17-21.pdf.

[3] GCF. 2017. Guidelines for enhanced country ownership and country drivenness. This document is as adopted by the Board and contained in annex XX to decision B.17/21. https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/guidelines-enhanced-country-ownership-country-drivenness.pdf.

[4] There are currently 147 Designated National Authorities registered with the GCF. See: https://www.greenclimate.fund/about/partners/nda (revised August 20, 2020).

[5] https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/governing-instrument.pdf (revised July 30, 2020).

[6] Ídem.

[7] Henrich Boll.2014. Strengthening country ownership, country driven approach, direct access.

[8] We note that a simple reference to “multi-stakeholder” engagement cannot satisfy or guarantee the effective participation of Indigenous Peoples. This is true for several reasons, the first is that Indigenous Peoples are “rights holders” and our rights to self-determination, land, territories and resources, traditional knowledge, Prior, Free and Informed Consent it is recognized by international law, enshrined in ILO Convention 169 and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

[9] https://www.greenclimate.fund/document/indigenous-peoples-policy (revised June 15, 2020).

[10] GCF. Project portfolio. https://www.greenclimate.fund/projects/dashboard.

[11] Letter of the International Forum of Indigenous Peoples on Climate Change to the Board. October 22, 2015 at the 11th. Board session.